A Record That Adds Color - S2/E2

[Note: The #52Ancestors in 52 Weeks challenge can be found on Amy Johnson Crow’s Generation Café FB site - HERE - https://www.facebook.com/groups/generationscafe. The stories posted there are terrific.]

OK, I guess it looks like only my second post in the #52Ancestors in 52 Weeks series might violate a rule. This post is not about an ancestor and the record I want to discuss is not about a family member. Nor is the record I am writing about a particularly old record – it’s a photo I took just last year.

But I found myself thinking in this challenge about how genealogy and family history can lead us down paths that aren’t always quite what we expect. This post is about context. It is about life in the South, and how the records we stumble upon can often tell us unexpected things about the places and times in which our families lived.

Like many bitten by the family history bug, I have a fascination with graveyards, the stone records they contain, and the stories hidden behind those tombstones. All of this is a bit of context for how I wound up roaming around two old church graveyards less than 10 miles from where we currently live in Apex, NC, and pondering the lives of Eugene Daniel and Gertrude Stone, their families, and their communities.

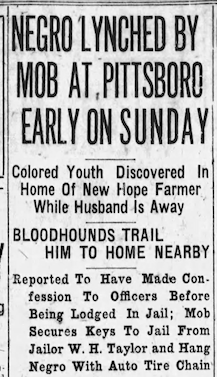

Here’s the photo/record:

These were two lives that collided. And nothing was ever the same.

John Daniel was born on May 6, 1872, and married Ida Mary Rogers (born on May 1875) on December 15, 1892. They proceeded to have 13 children.

On September 12, 1921, a young African American boy named Eugene Daniel turned sixteen. Although he didn’t attend school, his days were full, as he spent his hours working on his father’s farm on Farrington Road in New Hope Township, North Carolina. He was never alone at home; the eighth born out of thirteen children — five boys and eight girls — Daniel worked on the farm alongside his parents and siblings and helped to raise the younger members of the family. Though large and labor-oriented, the family was close-knit and fun-loving. They were largely independent, as the father, John Daniel, owned his own farm, but they still connected with members of the larger New Hope community when they ventured into town, visited the county seat of Pittsboro, or took their produce to market. (UNC Department of American Studies Honors Thesis by Morgan Vickers —this is a terrific piece of micro-history — I wish it had been published somewhere.)

Walter Robert Stone was born in 1880, and his wife Minnie Moore was born in 1882. Walter and Minnie were married in 1902 and had two children, Gertrude and Ernest. Gertrude Stone was born on April 15, 1904, and her brother Ernest Frank Stone was born two years later, on November 12, 1906.

Both families had been in North Carolina for generations. The families lived next door, and the children grew up together. (In the Census record, John Daniel is listed on the page immediately after the Stone family, and the rest of the family continues on the next page.)

Gertrude and Ernest attended Pittsboro schools. The Daniel children could all read and write — they had been taught by their mother — but the demands of the farm meant that school was not an option.

Both families lived anonymous lives typical of farming families in the early 1900s. The families only appeared in the local newspapers twice before September 1921. In January 1921, Ernest was "badly kicked" while "cranking a car." In May 1921, Gertrude performed at the High School's baccalaureate ceremony, performing a piano solo, "Over the Top," by Rolfe. Despite their prolific numbers, the Daniel family never appeared in the local newspaper.

Until September 1921.

September 17 wasn't initially a day of any particular importance.

The Daniel family—adults and children—started the day early. Breakfast was basic—maybe cornbread, grits, or leftovers from the previous night's meal. The family headed to the tobacco fields as the first light filtered through the trees. The air carried the earthy scent of tobacco leaves, particularly so since harvest was only a week or two away.

It was very hard work, and I remember thinking this is something I didn’t want to do for a living. It was very hot but it was a lesson in perseverance and strength and endurance... [T]hat was their primary source of income. They were pretty well off and had a big house. They grew everything themselves. They had hogs, cows and horses. They were a really self-sustaining family and they went to the market for some things and they made their own clothes. The family worked the farm every single day, particularly in the summer, leading up to harvest time in late September. (Morgan Vickers interview with a Daniel family descendent)

Gertrude and Ernest likely had a more relaxed start to their day than the Daniels children. After a few chores, they grabbed their books and headed out the door. As they left, their mother, Minnie, called, "Straight home after school. We'll be having supper early; your father is going coon hunting with the boys tonight."

Walter Stone had been looking forward to the hunt. It was a chance to get away for a few hours from the drudgery of farm life. The moon played a crucial role. A full moon meant better visibility, while a new moon required extra caution. As darkness settled, the coon hunters gathered their gear. Lanterns, sturdy boots, and trusty dogs were essential companions.

The coon hunters ventured into the woods, following well-worn trails. The forest was alive with sounds—crickets, owls, and rustling leaves. Specially trained coonhounds led the way. Their keen noses detected the scent of raccoons. Handlers followed, listening for the dogs’ barks.

It wasn't long before the dogs picked up the scent. The hounds cornered the raccoon and treed it. Walter and the other hunters followed the barks to locate the tree. The eyes of the coon reflected the light of the lanterns, and a few members of the party who were more agile than the others scaled the tree and used poles to force the coon into a burlap sack. After a few repetitions, the hunters gathered around a campfire to retell stories of the hunt and, truth be told, share a bottle of moonshine.

Back at the homes of the Daniels and Stone families, the darkness came quickly with the sunset at 6 o’clock, and a sleepy calm descended over both homes as the lanterns and candles were extinguished.

It is unclear what happened next. What is clear is that after everyone was asleep, Eugene Daniel walked quietly next door, entered the Stone house, and quickly went to Gertrude's room. He didn't touch her. It is uncertain why Eugene went to her room. According to some accounts, he and Gertrude had a relationship of some sort. Others speculate that Eugene was trying to find the bedroom of a girlfriend who worked as a maid in the Stone home. What is clear is that Gertrude possibly screamed after seeing a visitor in her room, which woke up her mother and brother. Eugene got scared and ran off.

Morgan's thesis summarizes what happened next more than I could ever hope to do.

It is unclear what time Walter returned home from his hunting trip, but the Stone family, without the protection of the father, didn’t make any efforts to chase the perpetrator or inform anyone of the incident on their own. The newspapers report that when the father returned to his family, they told him about the incident, and he immediately left home once again to inform community police officers. New Hope Township was a small hamlet in Chatham County and thus did not have its own police force. Therefore, Walter had to travel to the county seat of Pittsboro, five miles away, in order to seek the help of law enforcement officials.

Several hours later, the dogs “were placed on the tracks left by the negro as he left the Stone residence.” The bloodhounds led the officers, as well as an accumulated mob of ‘indignant citizens,’ along the foot tracks reportedly left by Daniel. After trailing him for “some distance,” the police cornered Daniel and captured him…His reported arrest charge was that he entered the Stone home with the intention of “criminally assaulting’ a white girl.” (Morgan Vickers thesis).

No one had been hurt in any of this. Yet. But anyone who has read To Kill a Mockingbird knows what would happen next once the lives of a black teenage boy and a white teenage girl collided.

At about 2 o'clock in the morning the following day, a group of 50 surrounded the jail in Pittsboro, got the keys to the cell, and dragged Eugene out of town.

Upon finding a suitable tree with “a convenient limb” on the side of the road near Moore’s bridge, the men fastened an automobile tire chain around the neck of Daniel. In one swift motion, they swung the other end of the chain over the limb of the tree and hoisted the boy. It was not the chain around his neck that strangled the life out of him, however; the mob of men fired round after round at Daniel, “fill[ing] his body” with bullets until he died. The body of Daniel, “still dangling from the end of the chain,” was discovered by members of the greater community at about 10 o’clock in the morning. Newspaper accounts report that over a span of two hours, between several hundred and several thousand people visited the scene of the lynching. They all ventured to the body ‘in automobiles and other conveyances and even on foot, all striving to reach the scene in time to view the body before it could be taken down…Pittsboro police officers did not arrive until noon, and thereby dispersed the accumulated crowd. (Morgan Vickers Thesis)

It was Sunday morning in a church-going community.

In the immediate aftermath of the lynching, local papers covered the immediate story, often getting Eugene’s name wrong and usually couching the story in the context of community “frustrations” about rising crime. Per the Hickory Daily Record, "Several violent crimes committed recently in this county are thought to be responsible for the lynching, much indignation having been expressed by the residents."

After the immediate first round of stories, everyone stopped talking about the events of late September 1921. Within a month, there were no further articles about the lynching. The County Coroner and a jury found no one responsible, even though a mob of 50 had committed the crime and a thousand people had convened on a Sunday morning to witness the result, most likely many of them on the way to church. Like many lynchings, everyone knew who did it, and no one was ever held accountable. And the community officially pretended that nothing unusual had happened.

So, what are we to make of this a century later? What does it say about the whole question of how we “remember” history — and who does the remembering? And as family historians, what is our role in helping our families move beyond just the facts — and help them understand the context in which people lived?

As I realized when writing Immigrant Secrets, trauma leaves a long tail. And trauma is not just personal, but collective. I'll leave it to others to debate whether it is genetically carried. But I do think trauma is inherited and passed from generation to generation.

The trauma of the history of lynching upon the African-American community is one that I cannot even begin to understand. It was one of the reasons for the massive migration north of African Americans in the mid-1900s. “The Talk” that is given to young boys has many roots, and the collective trauma of more than 4,000 lynchings is a very significant one.

At the micro level of the two families involved, their futures evolved in a way one couldn’t have imagined in 1921. Reading between the lines, it seems — as is often the case — that the victims exhibited far more grace and courage than the perpetrators.

First, the Stone family. Newspaper reports said that while Gertrude received no injury, she was “upset” and frightened and “nervous” following the lynching. She and her brother lived the rest of their lives close by their parents. Both married, and neither had children.

The story of the Daniel family is very different. Their history in the wake of the lynching is a long and prolific one; the nine surviving Daniel children leave an incredible legacy, one that says something about overcoming trauma. It doesn’t make it go away, but it demonstrates how victims survive. The life of Eugene’s older brother John T. – who was 19 years old at the time of the lynching and must have been particularly impacted by it – is a good example:

John T. was more than committed to the educational system. He attended local public schools for his primary education, graduated from the Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia, North Carolina, and then went on to receive his Bachelor of Science and his Doctor of Medicine degree from Howard University. He was also the first African American to serve as the President of the Board of Medical Examiners. Likewise, his son, John T. Jr. served more than 30 years as the principal for the Pender County Training School in Rocky Point, North Carolina, founded the Southeastern School Masters Club, and was a member of the Board of Directors of the North Carolina Teachers Association. (Morgan Vickers thesis).

I grew up loving To Kill a Mockingbird. There are many parallels to the story of Mayella Ewell and Tom Robinson and that of Gertrude Stone and Eugene Daniel.

But one person is missing in the real-life version of this story.

There was no Atticus to hold up a mirror to the sins of the guilty.